In Bits & Pieces, I share some brief insights, sparks of creativity and interesting lessons that may or may not constitute further, more elaborate work. Below you can read the most recent ones!

Optimal plant soil composition calculator

How can I determine the best soil composition for my plants? This page introduces an Excel tool to calculate optimal soil mixes for various plants.

Different plants from different environments thrive best in different soils. But how can you determine the most suitable soil composition based on those that you own? Blow, I introduce an excel spreadsheet that will help you do exactly that!

Interface

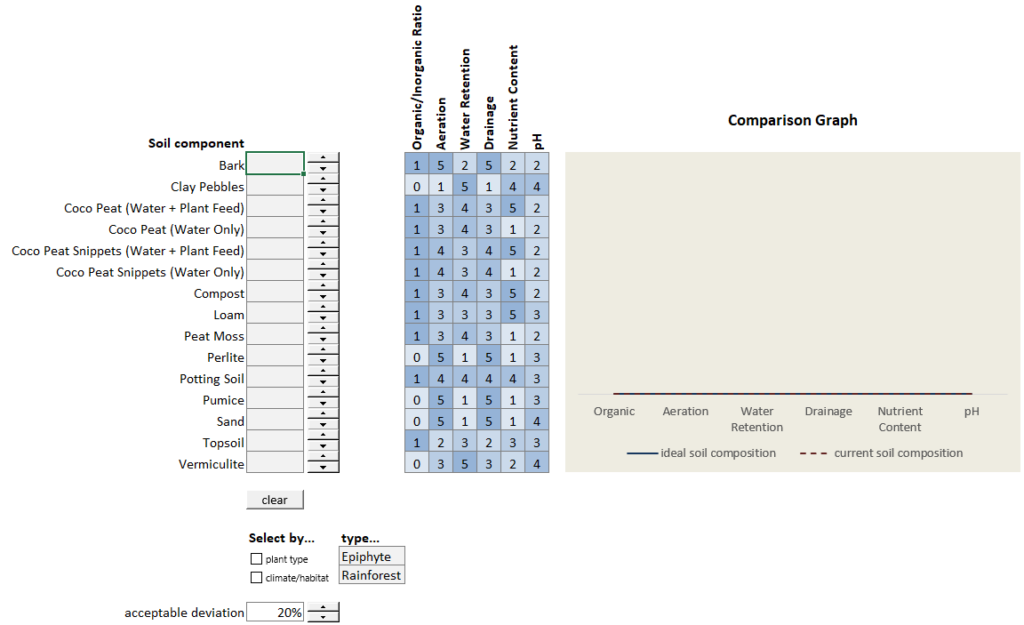

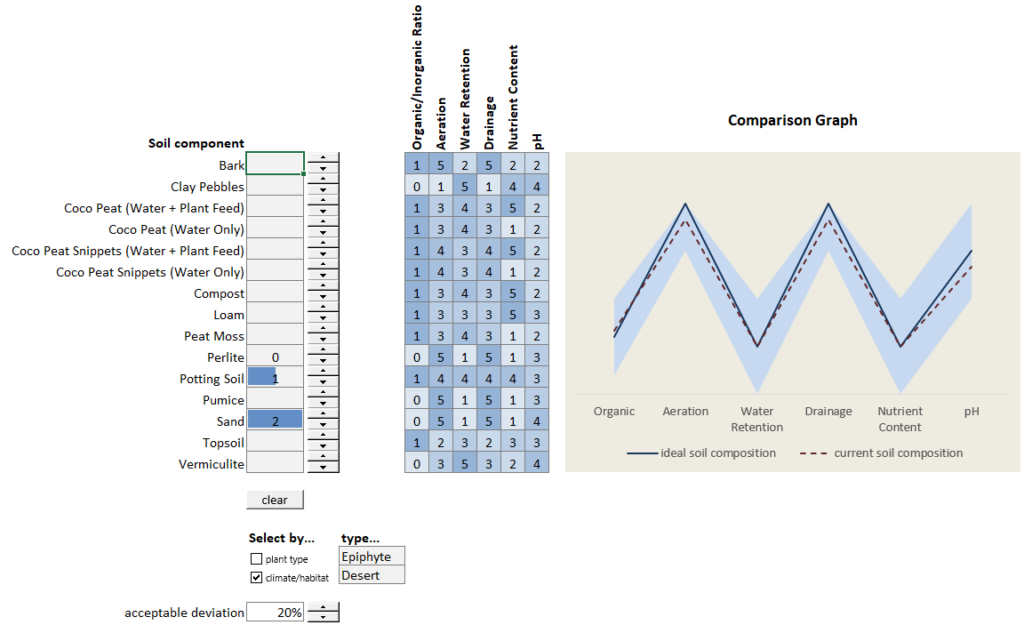

Below, you can see the interface on the first sheet of the workbook. In order for it to work, you will need to trust the file and enable macro’s (this is required for the button’s click-functionality).

You can select either a plant type or, when you are not sure about the plant type, the environment in which it typically grows. Click the checkbox for which option you would like the calculator for work, and use the drop-down under ‘type’ to select your choice.

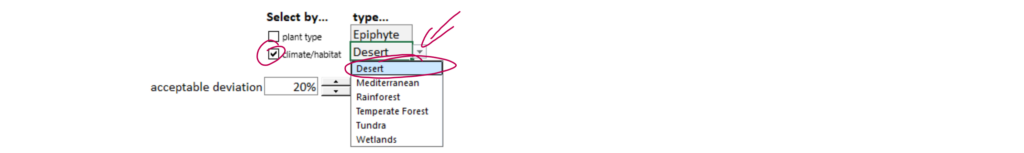

For example, below, I selected ‘climate/habitat’ for the selection category, and then ‘desert’ for type.

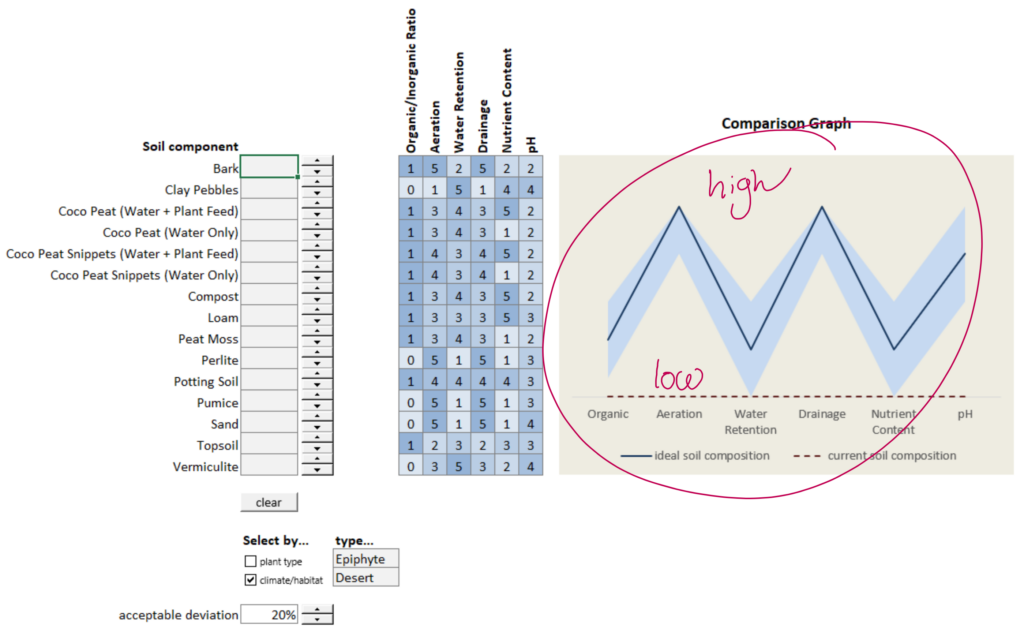

Once you’ve done that, you will see that a graph has appeared in the box on the right. This graph shows your ideal soil composition, considering six criteria:

- the ratio organic/inorganic material,

- the soil aeration (how easily oxygen can make it to the roots),

- water retention capacity (how much water can the soil absorb),

- drainage (how easily water can pass through),

- nutrient content, and

- pH-level.

Except for the organic/inorganic share, where the ratio is a value between 0 and 1, each criterion ranges from low (1) to high (5).

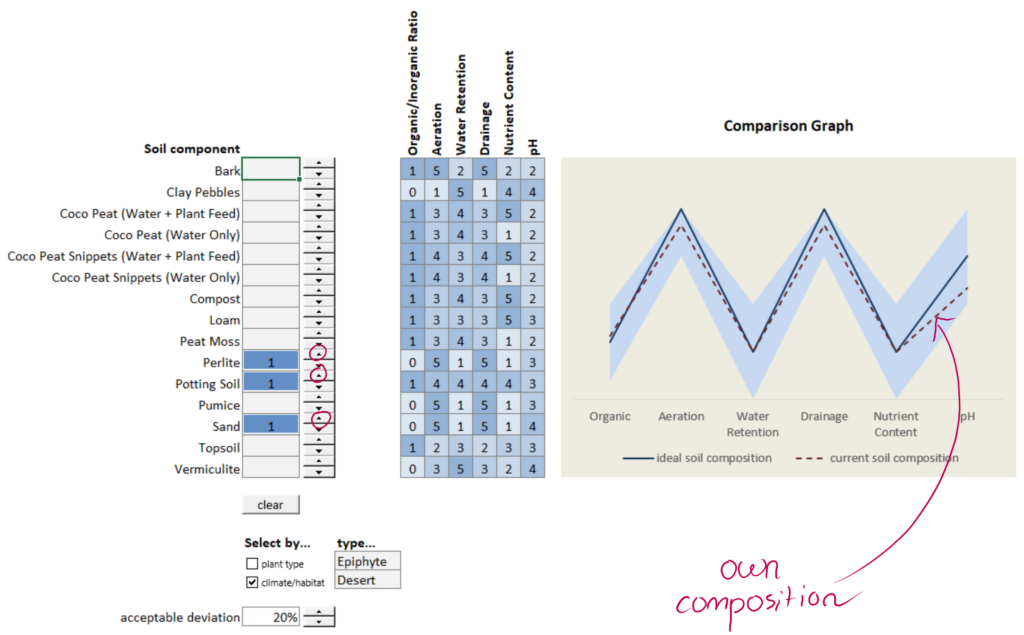

Now, on the left, you see a number of soil components. Using the up and down buttons beside the input cells, you can add or remove ‘one part’ (i.e. one cup, one shovel) of that particular type of soil.

When you do that, you will see another (dashed) line appear in the graph. This line resembles the characteristics of your current soil composition.

By adding and removing parts of soil that you have access to, you can try to get as close to the ‘ideal’ line with your own unique composition.

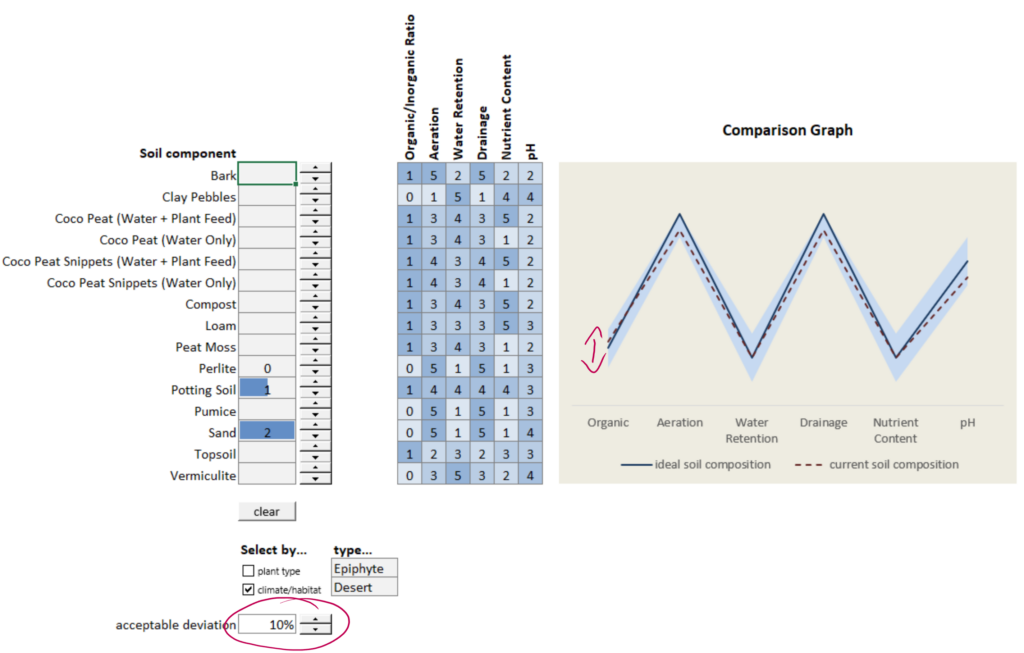

Taking our ‘desert-type’ example, I see that I can get pretty close to the ideal soil composition by adding equal parts of sand, perlite, and potting soil.

Of course, you may not have perlite available, or you simply find it too expensive. No problem! We see that by replacing one part perlite with another part sand, we get similar results.

You can ‘up’ or ‘down’ the ‘acceptable deviation’ percentage at the bottom of the sheet to increase or decrease the blue area in the graph. This is an handy indicator to determine whether your current soil composition is ‘good enough.’

One important side-note: all the data used in the spreadsheet was provided to me by ChatGPT. While I did not check the data, I haven’t seen any strange suggestions in the results. Nevertheless; use the sheet with caution!

And one last thing: I protected the first worksheet to make sure you do not break it. If you want to change things, you can easily lift the restrictions (I did not use a password to protect it).

That’s it! You can download the calculator via the link below. Have fun planting!

The story of our mind

How can I manage my thoughts effectively? This page explores the nature of thoughts and provides exercises to help unhook from negative thinking.

Like feelings, we cannot control our mind. Thoughts emerge from our sub-consciousness. We have no agency or control over them. Research shows that eighty percent of our thoughts have some negative aspect to them. Having negative thoughts, it seems, is more of a rule than and exception.

Thoughts are the mental form of speech or text. Together with images and memories, these comprise our ‘cognitions.’ Thoughts are often stories about how we see life. They include opinions, attitudes, judgements, ideals, beliefs, theories, morals, viewpoints, and assumptions. And from them, we conceive future prognosis, plans, goals, wishes, desires, aversions, and the like.

In ACT, we do not look at the truthfulness nor the attitude (positive vs negative) of the thought. We are only concerned with whether they contain something useful. In fact, trying ‘not to have’ negative thoughts by pushing them away or changing them is merely a ‘struggle’-strategy.

The reason this will not help you is because there is no ‘delete button’ in the brain. The brain changes by addition, not by subtraction. It changes by laying down new neural pathways on top of the old ones. That is the only thing we can work at, establishing new connections in our brain.

Negative thoughts can become problematic. For example, when we obey or accepting them as absolute truths. In such cases, we ‘fuse’ with our thoughts. They dominate our awareness to the extent we cannot focus on something else, or they dominate our behaviour in self-defeating ways. The latter often leading to self-fulfilling prophecies.

In some scenarios, it can even be useful to get hooked by our thoughts. For example, when we make plans or solve problems, or daydream during our summer vacation. Again, when ruminating helps us get closer to being the person we want to be, we should do it. In other cases, it is likely unhelpful.

Exercise: hands for thoughts

Imagine that all you enjoy in in front of you, as is all the unpleasantness of life. Then, open your hands in front of you, like a book, and imagine they contain all your thoughts, images, and memories.

Now, raise your hands to your face, until they are covering your eyes completely. What does the world look like when you peer out through the gaps between your fingers? This is what it is like to be hooked by your thoughts.

Lower your hands and look around you. What do you see and hear? This is what it is like to defuse from your thoughts. How would you experience others, and others experience you, when you can be aware of everything?

The overly helpful friend

Although it may feel very different, your mind is actually trying to help you. For example, by thinking through all potential future scenarios to prepare you for them. Or trying to learn from past events by going through them, over and over.

Similarly, judgements try to make the world black and white for easy navigation, self-criticism to help us to change our behaviour. Your mind is giving you all kinds of reasons not to do something, to spare you the pain or discomfort that might arise.

Under every thought is the intention to help us. Our mind tries to protect us, help us meet our needs and avoid pain, or alert us to important things that demand our attention.

Exercise: unhook from your thoughts

Recall an upsetting and recurring self-judgemental thought of the form “I am x.” Now focus on that thought and buy into it as much as you can for ten seconds.

Next, take that thought but, in front of it, insert this phrase: “I’m having the thought that I am x.” And then: “I notice I’m having the thought that I am x.” What happens? You can use this technique with any difficult thought that tends to hook you. Naturally, this goes for positive thoughts as well.

Exercise: unhooking with music

Again, bring to mind a negative and often-occurring self-criticism and buy into that thought completely. Notice how it affects you. Then, ‘sing’ the thought to yourself on the melody of happy birthday, or jungle bells. Does that change your experience?

By taking the thought and putting it to music, you experience its true nature. You realise that, like the lyrics of a song, it is nothing more than a string of words.

Exercise: unhooking by naming the story

Another way to unhook is to identify your mind’s favourite stories and give them names. For example, the “I am anxious”-story, or the “I can’t do it”-story. When your stories show up, acknowledge them by their name. Once you have acknowledged a story, just let it be.

Exercise: unhooking by naming the process

When you are plagued by multiple different thoughts, it can be more effective to name the process, rather than each thought itself. For example, “I’m noticing my mind worrying,” or even just “thinking.”

When you are overwhelmed by thoughts, it might be helpful to ‘drop anchor’ first. When you hear yourself say “this isn’t working,” recognise that as a thought as well!

Dropping anchor in mental storms

How can I manage overwhelming emotions? Learn to ‘drop anchor’ by acknowledging thoughts, connecting with your body, and engaging in the present moment.

Storms of painful emotions and distressing thoughts are often overwhelming. We cannot fight the storm, but we can learn to ‘drop anchor.’

To drop anchor, we first need to get acquainted with the practice of ‘noticing and naming.’ This is the practice of noticing your thoughts and feelings and naming them in a nonjudgmental manner. Doing so activates the prefrontal cortex, which moderates the other parts of the brain that amplify the storm.

For example, you might say to yourself “I’m noticing anxiety,” or “Here’s an urge to smoke.” Saying “I’m noticing anxiety” instead of “I’m anxious” helps us to step back a little. After all, we are noticing the feeling, the feeling does not comprise us. The same holds true for thoughts. For example, “I’m noticing the thought that I’m a loser” can be observed with curiosity, “I’m a loser” cannot.

Dropping anchor

Dropping anchor follows a simple three-step formula:

- Acknowledge your thoughts and feelings,

- connect with your body, and

- engage in what you are doing.

The best way to lean this practice is, again, through practicing the following exercise.

Exercise: how to drop anchor

The effect is best experienced when you bring to mind something that’s difficult in your life today. See if you can tap into the storm that accompanies it.

Acknowledge your thoughts and feelings

Tap into your childlike curiosity and acknowledge whatever is showing up inside. Thoughts, feelings, memories, sensations, urges… Use a term like “I’m noticing” or “here is” to name whatever you notice.

Connect with your body

Try to find a way that allows you to experience your body, most clearly and accessibly. You can focus on your breath, or the pressure of your feet onto the floor. You can also move: stretch an arm or tap a finger, as long as you can be very aware of the movement itself.

Keep in mind that you are not trying to push away your difficult thoughts and feelings. Nor are you trying to distract yourself. The aim is to keep acknowledging your thoughts and feelings and at the same time tune into your body. This will give you more control over your physical actions so you can act more constructively while the emotional storm lights up.

Engage with what you are doing

Once you have settled with the sensations inside of you, connect to—experience—where you are in the world. What do you hear, smell and see? Can you bring your full attention (back) to what you were doing?

Some people first connect with their body, and then acknowledge what is going on inside, and then Engage in what they are doing. That is fine too. You can experiment with your own order, ways of naming, and connecting with your body or settling into the outside world. Try to find what seems to work for you!

You can practice this on command (bringing up moderate storms as through the exercise above) or at other moments throughout the day. For example, whenever you notice you feel anxious, angry, irritable, worried, or sad. Also practice this any time you are unfocused, distracted, or on automatic pilot. This will also help you refocus and engage.

The more you do this, the better, and the better you will be prepared for the heavier emotional storms. Take as many moments as possible during the day, no matter how small, to practice.

What to do after dropping anchor

After dropping anchor, take a moment to reflect on what you were doing. If it was a ‘toward move,’ keep doing it while giving it your fullest attention. When you do that, you will give it your best and it will yield the highest result. If it was an ‘away move,’ stop, and reflect on the situation. Realise who you want to be and find a way to act accordingly.

What it feels like to drop the struggle

How can I stop struggling with difficult thoughts and feelings? Learn an exercise to manage and accept your thoughts for a clearer mind.

When difficult thoughts and feelings arise within us, our immediate instinct is to struggle. But like quicksand, struggling only makes things worse. The alternative is best understood through an exercise.

Exercise:

Imagine that in front of you is everything that matters to you. This includes both the enjoyable, pleasing aspects of life, and the difficult, unpleasant ones.

Grab a book, and pretend that it contains all those difficult thoughts, images, memories, feelings, emotions, sensations, and urges that you usually tend to struggle with.

Grip the book with both hands and hold it as far away from you as possible. Straighten your arms fully (no bending at the elbows) and extend them as far as possible. (This should be effortful; if it is not, you need to extend more, push harder.)

Maintain this position for at least one minute. As you do so, notice with curiosity how you find this experience. Note what kinds of thoughts and feelings show up.

Now imagine doing this exercise all day long, for hours on end; how devastatingly exhausting would it be? Imagine trying to do anything at the same time as doing this exercise. How much would it distract you from what you are doing? How much would you miss out on?

This is what we do when we struggle with our thoughts and feelings. We invest massive amounts of time and energy in pushing them away. This is tiring, draining, and distracting. We cannot be present, we cannot live.

Now let us try doing something different.

Again, pretend this book is all your unwanted thoughts and feelings. And again, push this book away from you, as hard as you can, for one minute straight. Then stop pushing and immediately rest the book on your lap. Notice what you can see and hear around you.

What difference does it make? What was it like to stop pushing?

When we stop struggling and make room for our thoughts and feelings, we do not fight them, nor do we let them push us around. Our mind becomes clear. We can invest our time and energy in toward moves. We can do the things we want to do better, and we experience life more clearly.

We can suddenly see our thoughts and feelings for what they are; pointers that tell us something meaningful.

The reinforcing cycle of the happiness trap

What is the vicious cycle of happiness trap and how to escape it? Discover strategies to manage unwanted thoughts and feelings, and improve your well-being.

We have little control over our thoughts and feelings, especially in challenging situations. Yet, in western society, we tend to feel stupid, weak, or inadequate when our attempts to control our thoughts and feelings fail.

This myth has emerged from the fact that in the outside world, we can control a great deal of things. Furthermore, when we are kids, we are told not to cry, to ‘cheer up,’ to not be scared, to ‘not think’ this or that… We are made to believe we can in fact control these things. No one has told us that they cry too, and that this is a perfectly natural thing to do.

We rarely speak of what really goes on inside our heads. And because we do not, we perceive ourselves to be inadequate for not having our own thoughts in order.

Vicious cycles

In this domain, solutions can become our problems. Trying hard to avoid, get rid of, or escape unwanted thoughts and feelings leads to more unwanted thoughts and feelings. This is the struggle strategy in action. It can take one of two forms:

Fight strategies:

- Direct suppression of unwanted thoughts and feelings.

- Arguing with your negative thought—trying to prove them wrong.

- Trying to take charge of your thoughts and feelings, to ‘snap out of them,’ or try to force yourself to be happy when you are not.

- Bullying yourself through hard self-judgement: “don’t be so pathetic.”

Flight strategies

- Opting out of situations or activities that trigger uncomfortable thoughts or feelings.

- Distracting yourself of the thoughts and feelings by doing something else.

- Avoid or get rid of unwanted thoughts and feelings through substance use.

These strategies can be helpful or even useful—emotional intelligence of sorts. Often, though, we use them to the extent that the net effect is negative. They become ‘away moves,’ distancing us (even further) from the person we want to be.

Excessive experiential avoidance comes at three big costs:

- These strategies eat up time and energy that could be invested in more meaningful, life-enhancing activities.

- We develop additional feelings of hopeless, frustration or inadequacy because the unwanted thoughts and feelings keep coming back.

- We lower our quality of life over the long term (we move further away from who we want to be).

Sometimes struggle strategies are automatic and unconscious. For example, when we experience intense pain our vagus nerve literally numbs us. It ‘cuts off’ our feelings to spare us from the pain. This gives rise to other unpleasant feelings: numbness, emptiness, hollowness, or a sense of being ‘dead inside.’

This is the ‘happiness trap.’ To increase our happiness, we try hard to avoid or get rid of unwanted thoughts and feelings. The more effort we put into this struggle, the more difficult thoughts, and feelings we create—the more unhappy we become.

Exercise: personal strategies

To really grasp the above, we need to identify which strategies we ourselves commonly apply. An exercise to do this is outlines below.

What have you tried?

- Start by finishing this sentence: The inner experiences I most want to avoid or get rid of are… Where ‘inner experiences’ can be anything like thoughts, feelings, emotions, memories, urges, images, and sensations.

- Write an exhaustive list of everything you have ever tried to avoid or get rid of these unwanted inner experiences. Think of both conscious and unconscious strategies. Use the list of flighting and fighting strategies above to produce as many as you can.

How has this worked out in the long run (what were the gains)?

Many struggle strategies give you short-term relief from painful thoughts and feelings. But do they permanently get rid of those unwanted thoughts and feelings?

What have you missed (what were the costs)?

When we use these methods inappropriately, they have significant long-term costs. Consider: When have you excessively or inappropriately used them? What have these methods cost you (health, money, wasted time, relationships, missed opportunities, work, increased pain, tiredness, wasted energy, frustration, disappointment, and so on)?

How many of these methods give you relief from pain in the short term but keep you stuck or make your life worse or have significant costs in the long term?

Struggle strategy or value-guided action?

Advice about how to improve our lives comes at us from all directions. We should find a meaningful job, do this great workout, get out in nature, start a hobby, join a club, contribute to charity, learn new skills, have fun with your friends, and so on.

All these activities can be deeply satisfying if we do them because they are genuinely important and meaningful to us. If we do these activities to escape from unpleasant thoughts and feelings, they will not lead to fulfillment—eudaimonia.

When you do things because they are meaningful to you, we would not classify them as struggle strategies. We would call them ‘values-guided actions’ (see chapter 10) and expect them to improve your life in the long term. If those actions are motivated to avoid or get rid of unwanted thoughts and feelings, they are struggle strategies instead.

How to escape the happiness trap?

The first step is increasing self-awareness. Notice all the little things you do each day to avoid or get rid of unpleasant thoughts and feelings. What are their consequences? Keep a journal or spend a few minutes each day reflecting on this.

The choice point

How can I make choices that improve my life? Learn to identify and make ‘toward moves’ that enhance your life and avoid ‘away moves’ that hinder it.

We are always doing something, even if it is just sleeping. And when we do something, we either do something that helps us move toward or away from the life we want. We can call those behaviours ‘toward moves’ and ‘away moves’ respectively.

During toward moves, we behave like the person we want to be, responding proactively to our challenges, and doing things that make life better in the long term. Toward moves are things you say and do that enhance your life. Things that make it richer, fuller, and more meaningful.

When we behave unlike the sort of person we want to be, doing things that keep us stuck or make life worse in the long term, we are doing ‘away moves.’ Away moves are not just constrained to the physical realm, but also include worrying, ruminating, obsessing, and overanalysing. Away moves make our lives worse, keep us stuck, exacerbate our problems, inhibit our growth, negatively impact our relationships, or impair our health and well-being in the long term.

Toward and away moves are highly personal and situational. The technical name for it is workability. Something that is a ‘toward move’ to some person in some situation, might not be in another, or to another person in the same situation.

Choosing toward moves can be hard, especially in difficult situations. When difficult thoughts and feelings arise, we easily get ‘hooked’ by them in one or two (or both) ways:

- Obey mode: our thoughts and feelings dominate us; they command our full attention or dictate our actions. We give our thoughts and feelings so much attention that we cannot focus on anything else, or we allow them to tell us what to do.

- Struggle mode: we actively try to stop our thoughts and feelings from dominating us. We do whatever we can to avoid them, escape from them, suppress them, or get rid of them. We may turn to drugs, alcohol or junk food, procrastinate or withdraw from the world entirely.

When our thoughts and feelings ‘hook’ us they pull us into away moves. We end up in a negative spiral that moves us further and further away from the person we aspire to be. The greater our ability to break the cycle—to unhook ourselves—the better life gets.

Cultivating this skill is what we will learn throughout this book. To work through it successfully, the following three strategies are paramount:

- Treat everything as an experiment. Bring an attitude of openness and curiosity to each experiment in the book. Notice your experience, try not to enforce ideas about how you are ‘supposed to feel.’

- Expect your mind to interfere. Your mind will try to protect you from uncomfortable thoughts and feelings in the short-term by pulling you away from the unknown. This prevents you form moving forward, toward the person you want to become. Be aware of what happens when it does.

- Practice is key. We cannot learn new skills by reading books about them. Books can help us get them, but they cannot give us the skills.

Exercise: complete a choice point

To grasp the choice point model fully, tag along the following exercise:

Identify hooks:

- Grab a piece of paper and draw two straight arrows diverging from one central point in the bottom.

- At the point in the bottom, write down the most difficult situations you are dealing with in your life today.

- Underneath those, write down difficult emotions that tend to recur in these situations.

- Write down any urges you struggle with, in response to those emotions and situations.

- Write down any unhelpful thoughts that tend to occur. These include self-judgements, beliefs, and negative predictions.

What are your away moves?

Alongside the left arrow, jot down what away moves you make, whether obey or struggle-driven, in response to the difficult thoughts and feelings written below. Again, include the things you do physically as well as the things you do mentally. Remember, away moves are things you do, not things you feel.

What are your toward moves?

On the right arrow, write down what you can (and do) do as toward moves. After that, write down toward moves you would like to start doing.

Life with Full Attention: Awareness of dhammas

‘Authentic happiness’ is what we experience when we get in touch with our virtues and strengths. It exceeds vedana of ordinary pleasurable activity. It is the fourth sphere of Buddhas four spheres of mindfulness. It is also the topic of the fifth week of life with full attention.

Dhamma can mean both ‘teaching’ and ‘truth.’ It is an awareness of experience in light of what we have learned. We are more happy, creative and tolerant when we act out of positive states of mind and emotion. If we want to experience authentic happiness, we need to learn to cultivate a positive state of mind. Mindfulness of Dhammas is about learning to establish ourselves in more openhearted attitudes, creative thoughts, and outward-looking volitions.

Practicing mindfulness of dhammas entails noticing and responding to what happens in our mind. It is the internal equivalent of changing the subject of a conversation. To be able to do this, we need to have developed a sufficient awareness of citta. When we do not know ourselves—our minds—sufficiently, we may ‘dampen’ our character. We try to be a nicer or more spiritual person rather than a more authentic version of ourselves.

We need to be clear about the forces we are taking on. Our habitual responses come from instinctive drives; self-preservation, power, status, sex, and greed. We need to be willing to feel these drives rather than to wish them away. It is from feeling and acknowledging them that we can decide on the best course of action.

Often, our habitual responses arise from genuine needs. We should look for those needs first. From those needs, we can strategise more helpful means for attaining them. When you notice a ruminating pattern in the mind, stop for a moment to find out what it is trying to tell you. See if you can respond to it in a constructive way.

Our aim is not to feel guilty or repress our instinctive reactions. It is to unlock the energy that lies within them.

When we desire something, we over-emphasize and romanticise the pleasurable aspects. We rationalise away the negatives, marginalise it, or dismiss it as unimportant. Our practice entails remembering that life has this twin aspect.

Our instinctive reaction to something unpleasurable is aversion. This reaction often overshadows any positive about the object of dislike. When aversion emerges, we should look for the positive, too, and imagine it clearly.

Mindfulness of shammas thus requires us to

- notice the state of mind we are in,

- create a gap of honest self-reflection, and

- decide on the best course of action.

Cultivating awareness of dhammas

The ‘five precepts’ of Buddhism are ethical guidelines—principles of training. Each has a negative aspect (what we are trying not to do), and a positive aspect (what we are trying to cultivate). These precepts are tools to develop virtues and strengths: kindness, courage, patience, honesty, and a willingness to learn. They are not ‘rules’ to constrain or confine us.

The precepts are as follows:

- refrain from harm—cultivate love

- refrain from taking the not given—cultivate generosity

- refrain from sexual misconduct—cultivate contentment

- refrain from lying—cultivate honesty

- refrain from intoxicants—cultivate awareness

We may start this week’s practice by taking an ethical inventory of our life. Consider each precept and explore which one(s) you can improve on most. Try to come up with specific examples, whether habits or not, where you can make a conscious effort to change.

Be fearless and completely honest with yourself. Your current responses only propagate your needs, there is no shame or guilt in that. It is, however, your responsibility to produce more healthy alternatives—in line with the precepts listed above.

If you make this practice a daily habit, you cultivate awareness of dhammas.

From this inventory, you can set out to take on a personal precept. For (at least) a week, try to work on one of the things you want to do less (or more) in line with the precepts. Make it actionable and specific, what will you do, and how will you make sure that you do it?

Acting against the precepts limits and constricts our awareness. We cannot be mindful with a troubled conscience.

The ‘four forces’ are how we cultivate mindfulness of dhammas from moment-to-moment. Practicing the four forces is the core challenge of this week.

- Eradicating already arisen unskilful mental states. Acknowledging and taking responsibility for being in a bad mood.

- Preventing the arising of yet un-arisen unskilful mental states. This entails being present and enjoying positive states of mind. It also entails self-care and keeping your life in order, such that practical disturbances do not get a chance. Neglecting good habits and slipping up on bad ones are early signs that we are headed for a negative state of mind.

- Cultivating the arising of yet un-arisen skilful mental states. Doing the things that we know put us in a positive state of mind. This entails practicing a life with full attention and getting our lives in order as well.

- maintaining already arisen skilful mental states. Care to not lose our mindful awareness when we are in a happy place. Do not get intoxicated (fifth precept) by our good mood!

In each, skilful mental states are positive mental states. Unskilful mental states are negative mental states. ‘Skilful’ makes clear that we are learning a craft; it will take time, application, and patience.

The mindful walk provides the perfect opportunity to assess which of the four forces is working on you. Practice the appropriate response to move toward (or stay in) a skilful state of mind.

Use your mindful moment or vedana journal cues to do the same thing. Assess your mind-state and see how you can improve or maintain it.

Below are the instructions for this week’s mediations: notice your state of mind and apply the forces.

- Day 1: settle into your body and feel your breath. Notice what happens in your mind when you lose contact. Acknowledge and accept whatever thoughts or mind-state arises.

- Day 2: cultivate awareness of where your mind wanders off to when you meditate. If you notice an unhelpful state of mind, see if you can cultivate the opposite.

- Day 3: look for pleasure within the breath. When you are distracted, see if the distraction beings you pleasure. When it does, see if you can experience the pleasure directly, without the surrounding imagery or story.

- Day 4: become aware of vedana around your heart: in your belly and chest. Reflect on a positive emotion; can you remember a time where you felt alive, connected, or absorbed in a pleasant activity? Notice any response in the aforementioned areas.

- Day 5: today, just sit still and try to do absolutely nothing.

- Day 6: bring your mind to people you feel grateful toward. Notice your inner response with complete openness to whatever arises.

- Day 7: Start by cultivating awareness of the breath. Then, bring to mind the things you already have. Bring to mind the things you like doing. Bring to mind your friends and what you appreciate about them. See if you can stay aware of this sense of appreciation, without losing awareness of the breath.

Fifth practice week

Having slacked a bit on my previous aspirations during the Christmas break, I am excited to start anew with the following practices.

Vedana diary

Whenever I feel a particularly strong vedana, or when I get my daily random reminder, I will write down:

- what I feel,

- where I feel it, and

- what might have caused it—which need was not met.

When the vedana is positive or negative, I will consciously look for the contrasting counterpart.

Daily meditation

I will follow the instructions provided in the book. Besides mediating in the morning, I will also meditate at night, followed by a ‘stream-of-consciousness’ in my journal.

Mindfulness moment

I will use my morning shower to assess my current mind-state. Whether positive or negative, I will try to balance it with the others’ thoughts.

Taking ethical inventory

During the weekend, I will take thirty minutes to an hour to take an ethical inventory of my life. For each precept, I will write down what I can do less and more for each.

Mindfulness walk

Since I have not improved on this habit at all, I will take the stairs whenever I arrive at work, and practice body-awareness there.

The happiness trap

This is a summary of the introduction of ‘The Happiness Trap’ by Russ Harris, which I will be exploring further in the upcoming days!

We all know that life is full of happiness and sorrow. Yet very few of us seem to be able to accept, and to live this reality. Our pursuit of happiness leads only to further despair, we are caught in a happiness trap. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) contains the knowledge and skills to escape this trap.

Our brains are hard-wired for worrying. Historically, the person that worried most (foresaw the most possible danger) would survive. As a result, we all spend a lot of time worrying about things that, more often than not, never happen.

In a similar sense, we have a strong biologically driven desire to ‘belong.’ To grasp this, we compare ourselves to others, or idealised versions of ourselves. Unfortunately, the digital age leaves us with a lot of (unfavourable) comparing to do.

In short: we are hardwired for psychological suffering. And to make matters worse, common beliefs about a ‘way out’ are inaccurate, misleading, or false.

- We believe that happiness is our natural state. In reality, we move through an endless spectrum of emotions. Love, joy and curiosity, are as normal as sadness, anger, and fear. From this false belief follows the next, namely that we believe that;

- when you are not happy, there is something wrong (with you). We assume that psychological suffering is abnormal. When we experience a negative emotion, we are ashamed about it and criticise ourselves for being weak or weird.

Along with these myths, there are two distinct definitions of what happiness actually entails:

- Happiness as a good-feeling: a pleasurable feeling of joy, gladness, or contentment. Hedemonia entails living life in pursuit of these feelings.

- Happiness as the experience of living a rich and meaningful life: clarifying what we stand for and acting accordingly. Eudemonia not some fleeting feeling but a powerful sense of a life well lived.

We cannot escape pain and fear, but we can learn to handle it much better. We can learn to “unhook” from it, rise above it, and create a life worth living, a life of Eudemonia. This book is here to teach you these things.

How organising your home can change your life

How can I organise my home to change my life? Discover how tidying up can improve your decision-making and bring joy to your life.

At their core, the things we like do not change over time. By putting your house in order, you can (re)discover what they are. When you put your house in order, you can discover what you really want to do. After all, the things you decide to keep are the things that bring you joy.

Tidying changes your life. Being in an environment in line with who you want to be—without distraction of clutter—sets you up for an authentic life.

Tidying improves your decision-making capacity. By taking an item in your hand and feeling whether it sparks joy, you train your ‘decision-muscles.’ Doing this hundreds or thousands of times creates a strength like you have never known.

When we get clear on the reasons for why we cannot let something go, we find that there are only two:

- an attachment to the past, or

- fear for the future.

This is a useful observation, because each time you are having trouble to discard something that does not spark joy, you can explore your inner world. When you are particularly prone to either of the two, chances are these interfere with other areas in your life as well, e.g. work or relationships. Exploring to what extent this is keeping you from living up to your full potential is worth the effort.

Whether we are caught up in the past, or in the future, we cannot see what we need now, at this moment. The best way to find out what we really need is to get rid of what we do not.

Facing and selecting our possessions forces us to confront our imperfections and inadequacies, and the foolish choices we made in the past. It is only when we take the things we own one by one and experience the emotions they evoke that we can deeply appreciate our relationship with them.

There are three approaches we can take toward our possessions: face them now, face them sometime, or avoid them until the day we die. The sooner we confront our possessions the better. If you are going to put your house in order, do it now.

There is greater happiness in life than to be surrounded by the things you love. Allow yourself this happiness and remove the noise that interferes with the happiness radiating toward you.

Human beings can only truly cherish a limited number of things at one time. Pour your time and passion into what brings you the most joy, your mission in life. Putting your house in order will help you find the mission that speaks to your heart. Life begins after you have put your house in order.

Benefits of owning less

When we have reduced the amount, we own and know where it is, we can tell at a glance whether we have something or not. When we do not, we can shift gears immediately and start thinking about what to do. We do not have to spend time searching for something we ‘might have somewhere maybe.’ Instead of suffering through the stress of looking and not finding, we act.

Your environment changes you

Much of this final part of the book is best summarised by another book that inspired me to read this one: ‘Willpower Doesn’t Work’ by Benjamin Hardy.

Hardy argues that the only way you change is by adapting to your environment. Getting your environment in order, then, is the key to getting yourself in order. Your mental and physical health, clarity on your life’s purpose and priorities… All follows from creating an environment that embodies who you want to be.

Storing things Marie Kondo style

How can I store things Marie Kondo style? Learn practical tips for decluttering and organising your space efficiently with Marie Kondo’s method.

When you have discarded everything that did not bring you joy, it is time to find a spot for everything that does. By giving each item a place, you assign each place an item. When that happens, it is less likely that a ‘thing without a place’ ends up there and invites further clutter around.

You only need to designate a spot for every item once. Decide where your things belong and when you finish using them, put them there. This is the main requirement for storage.

Storage: how to store

When it comes to the practicality of storage, there are only two rules:

- store all items of the same type in the same place, and

- do not scatter storage space.

You can follow the discarding categories for storage, or a broader system based on similarities in material. For example, ‘cloth-like,’ ‘paper-like,’ and ‘things that are electrical.’

If you live with your family, first clearly define separate storage spaces for each family member. Each individual’s storage should be focused in one spot. Having your own space makes you happy. Once you feel that it belongs to you, you want to keep it tidy. Everyone needs a sanctuary.

Storage: where to store

Clutter emerges from a failure to return things to where they belong. Storage should reduce the effort needed to put things away, not the effort needed to get them out.

When we want to use something, we have a clear purpose for getting it out and will go through the effort of doing so. It is the effort of putting things back that is difficult.

As such, it is best to store things in a single spot. When you do that, you do not have to think much about where to put things away.

Storage: next to, not on top

When it comes to storage, vertical is best. When you stack things on top of each other, you can keep storing indefinitely. Things on the bottom get squished and worn. Furthermore, retrieving an item will require two extra steps—removing and placing back whatever it was that was on top.

Storage: ‘solutions’

The only storage items you need are drawers and boxes. Create your own original combinations by matching an empty box to fit an item that needs storing. The best method is to experiment and enjoy the process.

The best way to store bags is in another bag. The key is to put the same type of bags together. Doing so means that you only need to take out one set whenever you need a particular bag.

Storage: routines

To avoid losing track of things, and to give your bags a well-deserved break, empty your bag every day. This is not as much effort when you have a place for all the things inside it.

Do not keep your soaps and shampoos in your bath or shower. Dry them up and store them away after use. These spaces will be tidier and easier to clean, and any ‘sludge’-buildup is prevented.

Similarly, your kitchen counter and sink are for preparing food and washing dishes, not for storing things. Put sponges and dish detergent underneath the sink. Keep oil, salt, pepper, soy sauce, and other seasonings in your kitchen cabinets. This will keep those things free of grease, and your kitchen much easier to clean.

Space can be noisy and tidy at the same time when it is overflowing with unnecessary information. Remove the product seals from your storage containers and tear the printed film off packages that you do not want to see. Your space will be much more peaceful and comfortable.

Another good habit to develop is to appreciate your belongings. Express your appreciation to every item that supported you. You will have a more grateful existence and take better care of what you own—extending your possession’s lifespan in the process!