What is overidentification? How do I stop overidentifying? This article describes overidentification and its relationship with social anxiety and stress, the effects of overidentification, and ways to manage it effectively.

Over the past couple of years, I’ve read countless books on self-improvement, self-sabotage, self-esteem and self-compassion, hoping to find a way to make my social experiences less stressful and more enjoyable overall. Putting their advice to practice, however, appeared impossible. Time and time again, I was too overwhelmed to remember, let alone implement, any of guidance provided. If anything, knowing what I did wrong made things worse, adding more stress rather than reducing it.

It was during a guided meditation session from Richard Lang that I learned about—or rather experienced—the concept of ‘identification.’ From further exploring this idea and a Vipassana 10-day silent retreat I realised that I, and maybe many others like me, have been fighting the wrong battle. While the symptoms resemble those associated with social anxiety, it was ‘overidentification’ that may have been the cause.

In this article, I will try my best to illustrate this notion of ‘overidentification,’ how it can cause excessive stress in social situations, and, perhaps most importantly, why common approaches to address social anxiety can be ineffective—even counterproductive instead.

To see whether you may be overidentifying, you can take a simple, 10-question overidentification test. It’s best to do the test before reading further to avoid an (unconscious) bias in your answers. The test takes about 5 minutes to complete and can be found here:

If you want to learn more about the setup of the test, you can find a dedicated background article here.

A definition of overidentification

Overidentification constitutes the tendency to identify excessively. When we identify with a person, we mentally put ourselves in their shoes. In a way, we adopt their ‘being’ in order to see the world from their point-of-view.

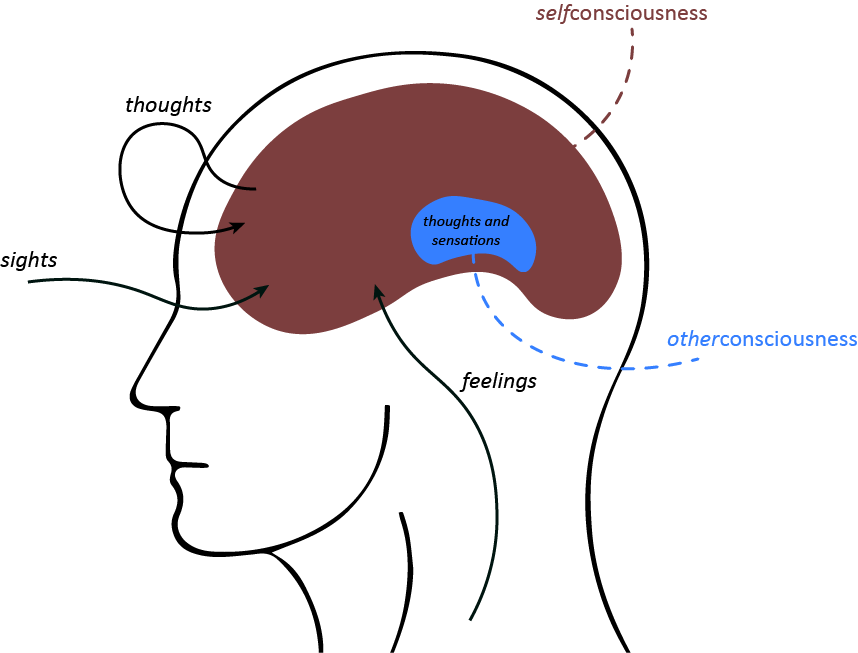

Metaphysically, we can understand this as follows. Our own consciousness is the open space in which all our thoughts and sensations appear. We can refer to this open space as our selfconsciousness.

When we identify with someone, when we try to see the world from their point of view, we create some sort of pseudoconsciousness within our own. This pseudoconsciousness tries to hear what the other person hears (such as ourselves talking), see what the other person sees (such as ourselves moving) and think what the other person thinks (such as liking or disliking ourselves). We can refer to this pseudoconsciousness as the otherconsciousness.

Seeing yourself do something embarrassing, hearing yourself say something stupid, or thinking about how others perceive you all emanate from the otherconsciousness. However, since they appear within our selfconsciousness, they are equally potent in inducing a neurophysical response, such as fear or shame, to inform our actions and decisions.

Experiencing identification

This whole concept is difficult to grasp on an abstract level, but more easily perceivable through experience. Hence, you may find the following exercise useful.

Stand in front of a mirror and take a few deep breaths. Then look at the person in the mirror for about one minute.

If you are like most people, you probably see some things that you don’t like. Maybe your hair (if you happen to have any) is a bit off, or you think your nose is too big… Or you see things that you do like; the colour of your eyes, your smile, skin tone…

These observations make you feel a certain way. For example, when you don’t like your hair, you may feel unattractive. Equally, when you like what you’re seeing, it’s quite likely that you will experience feelings of a more pleasurable nature.

In this case you are identifying with your mirror-image. You are creating an otherconsciousness in your head that looks at you from the mirror, and you are experiencing what you think that otherconsciousness would experience (e.g. rejection or awe).

This might still sound vague and complicated, but now try something else:

Keep standing in front of the mirror, but now put all your attention towards the feeling in the soles of your feet. Try to feel exactly where they touch the ground, how the pressure of your weight is distributed, what the temperature of the ground is… Take about one minute to really experience your feet, but keep your eyes in front of you, facing the mirror.

That probably felt a lot different, right? Even though your mirror-image was still within your line of sight, you did not experience any feelings because of the way you appeared. You may even wonder whether you were looking at all?

Now, let’s try a third perspective.

Again, look at your mirror image. But now, I want you to describe objectively what you perceive in the mirror. What are you seeing? Probably a person. What colour hair and eyes does the person have? What facial expression does it have? What is the shape of the head? Do this for about one minute also, trying to catch as many details as you can.

In this last part of the exercise, you have been perceiving without identifying. You still saw what you did in the first part, but it did not evoke any feelings or thoughts.

You may even have experienced the directionality of your perception differently. You might have experienced the first part of the exercise as if looking from the mirror image, the second part as not looking at all, and the third as looking from your own point-of-view.

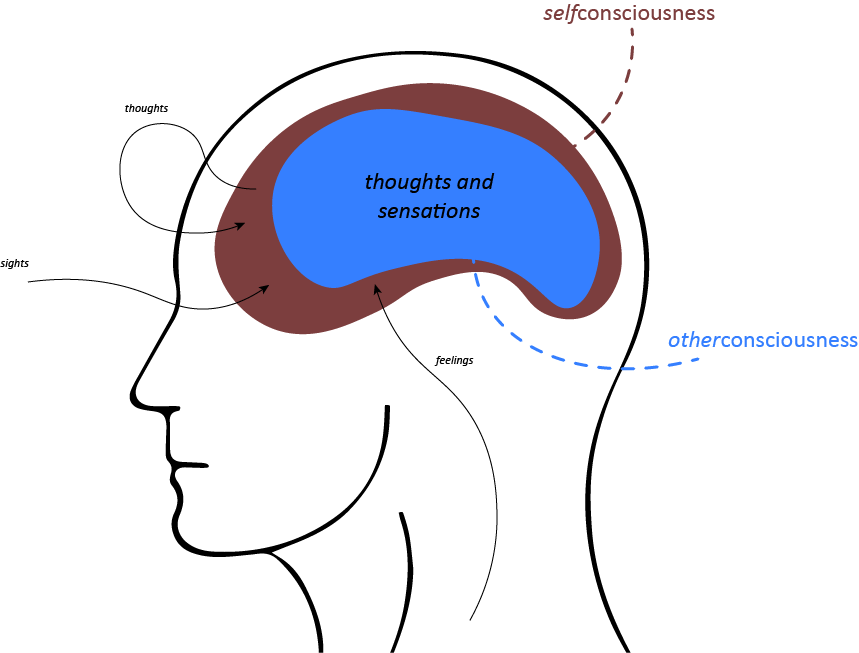

These perspectives correspond to the otherconsciousness (1), no consciousness (2), and the selfconsciousness (3) respectively. I’ve tried to illustrate how these would be experienced below.

It took me several 10-minute exercises like the one described here to fully ‘get’ this illuminating experience of changing perceptions. If you are overidentifying (indicated by a high score in the test), I highly recommend checking out the work by Richard Lang, based on the writings of Douglas Harding.

Specifically, in his series “The Headless Way” in the waking up app or on YouTube, he guides you through some similar experiments to help you perceive the difference between the otherconsciousness and selfconsciousness perspective.

The needs and consequences of identifying (excessively)

Identifying with other people, or your mirror image, is not a bad thing. It allows us to be empathetic, anticipate other people’s actions, and in general just function as a social being in society. Furthermore, a person who lacks the ability to empathize or identify with others entirely (a condition we might call underidentification) would exhibit traits of psychopathy.

However, identification is an automatic process, and in this article, I would like to steelman the case that it is possible to identify too much. This isn’t a deliberate act, but rather a habit you can develop in particular environments where identifying intensely with the people around you is necessary to ‘survive.’

What it means to overidentify

We can conceive identifying with someone as dedicating some of our mental bandwidth to construct an otherconsciousness within our own mind. From this otherconsciousness, we extract pseudo-thoughts and sensations that can help us to navigate the world. When we have a healthy degree of identification, the bandwidth dedicated to the otherconsciousness does not interfere too much with our own and does not override our sensations and thoughts.

However, our mental bandwidth is limited, so all the resources that are mobilised for constructing the otherconsciousness can no longer be used to serve our own. When a disproportionally large amount of space is dedicated to simulating the otherconsciousness, we lose the clear awareness of our own sensations and thoughts. It is in this situation that overidentification occurs.

In such a case, we can get overwhelmed when we are with others, have trouble deciding what we want, and often become agreeable to others.

When we overidentify

Overidentification will occur mostly in social, face-to-face interactions. However, we can equally well identify (and overidentify) with people that are not there physically, with animals, our environment, and objects.

It happens when we post something on social media (what will the internet think), when we imagine a though conversation we had in the past or a presentation we’ll give in the future. Even when walking through an empty street, you may experience how you are appearing and stiffen up.

Ever felt bad for throwing something away, or finding out you haven’t used something in a very long time? Chances are you are identifying with that object and how you think it might feel (even though the object does not even have the capacity to do so!).

These examples illustrate that when you are overidentifying, you may be overidentifying all the time. You may have forgotten how it feels to be fully and completely with yourself, and, possibly most concerningly, you may think this is simply the way things are.

Examples of overidentification

Below I’ve listed some illustrative examples of how overidentification may be experienced:

Constant tension in the presence of others and breaking eye contact prematurely. One’s own need for connection is trumped by the desire to avoid looking ‘weird’ from the otherconsciousness’ perspective.

Hypervigilance of people in one’s environment to feed ques to the otherconsciousness.

Being overagreeable to others: ‘not caring’ about what to do or eat. The lack of bandwidth for one’s own feelings and needs makes one appear indifferent to choices where others are involved.

A missing sense of self. Similar to the latter, constant overidentification makes it hard to connect to one’s own feelings and needs. In the long-run, this is experienced as a losing sense of self.

The feeling of being on autopilot in (intense) social interactions. As these interactions are dominated by the otherconsciousness, coming out of them may feel to the selfconsciousness as ‘waking up.’ The self appeared to be wholly absent during the interaction itself.

- Susceptibility to other people’s moods. Mentally putting yourself in someone else’s shoes involves copying their mood. This can manifest as both an upward (positive mood) as downward (negative mood) spiral.

Contrasting concepts: social anxiety and (over)empathisation

We should understand overidentification as distinct from social anxiety and from what we may refer to as overempathisation (excessive empathy), even though on the surface, the symptoms of either will appear to be the same.

The way I see it; social anxiety is often caused by negative thoughts and perceptions about oneself. It concerns the type of thoughts and sensations that (perhaps a healthy degree of) identification evokes, not the amount of thoughts and sensations and the mental bandwidth they exhaust.

In practice, these two are difficult to untangle. In social contexts, you can become paralised due to the overwhelmingly negative nature of thoughts and sensations or by the volume of thoughts and sensations that emerge—the effect is the same. When you suffer from this ‘social paralysis’ but do not have a particularly negative self-image, it’s more likely that overidentification, and not social anxiety, is the cause.

This is not to say that one necessarily excludes the other. Overidentification and intrusive thought- and sensation types can, and maybe often do, occur simultaneously.

In a similar light, we can think of overempathisation as the disproportionate weighting of the otherconsciousness’ thoughts and sensations when informing decisions or behaviour. Again, it is not about the amount of thoughts and sensations, it is now about how much value is attributed to them.

These distinctions are crucial, as the path to address them is completely different:

- Overidentification requires reducing the relative bandwidth given to the simulated perspective, e.g. using mindfulness to return to your own experience (more on this below).

- Social anxiety benefits from addressing the content of negative thoughts, e.g. through cognitive-behavioral therapy to challenge and replace them, or by learning to simply observe them for what they are.

- Overempathisation requires reevaluating the weight given to others’ emotions versus your own, e.g. through boundary-setting and asserting personal preferences.

If you have found the many ‘solutions’ to social anxiety to be largely ineffective, the above distinction may help explain why.

How to stop overidentifying

Of course, the big question now is how to stop overidentifying.

Following the theoretical analysis presented above, there are two strategies to pursue:

increasing the dominance of the selfconsciousness, e.g. by increasing awareness of one’s own feelings and thoughts, and

decreasing the dominance of the otherconsciousness, e.g. by catching your mind when trying to perceive yourself from another’s point-of-view.

In order to be able to do that, it is paramount to:

cultivate awareness of selfthoughts and selfsensations versus otherthoughts and othersensations.

Lastly, I already mentioned how overidentification is a habit that one develops over time in response to a particularly demanding environment. The first step should therefore always be to

investigate where the habit of overidentification has emanated from.

Understanding how this pattern emerged, and may indeed still be called for, is essential for breaking it down.

I have personally made significant progress through exploring different methods for each of the above. If this whole overidentification-concept resonates with others, I’m very happy to share about those in the future as well.