A lot of people are just barely short of obsessed with continued self-improvement, both in the mental and the physical domain. We eagerly look for the best habits to maintain and incorporate as many of them as possible.

If you are a bit selective, you will limit yourself to methods that are either scientifically proven (e.g. the positive influence of caffeine on focus) or, if you like living on the edge, methods that have at least shown some promising preliminary results (e.g. the health benefits associated with intermitted fasting).

However, our enthusiasm for self-improvement can make us blind to critically reflect on the things we are planning to implement (myself included, impulsively spending hundreds of euro’s on supplements). Here, I want to illustrate with a short example why it is therefor important to conduct self-administered experiments.

Let’s take the classic example of the effect of caffeine on cognitive clarity and mental focus. Many of us know that caffeine improves alertness by blocking adenosine, a neurotransmitter in the brain that promotes relaxation and sleepiness. However, for some people, caffeine can also lead to restlessness, nervousness, and jitteriness, which may reduce our ability to focus.

How can both be true at the same time?

Well, when something is ‘scientifically proven,’ this does not mean something is true 100% of the time. Taking again the example of caffeine, it only means that, on average, there is significant difference between those consuming caffeine and a control group (usually, this group has taken a placebo instead).

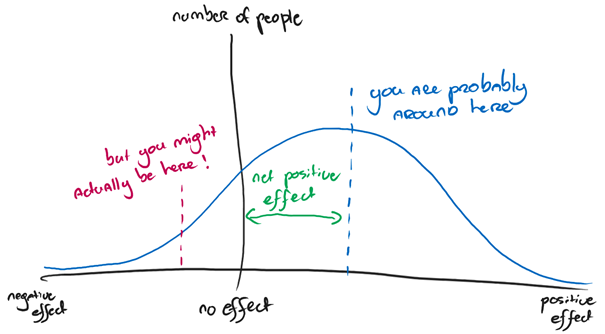

Furthermore, the distribution of how ‘focused’ people are needs to be normally distributed, meaning that the deviation from the average effect can be explained mostly by inherent statistical uncertainty. All of this is shown in the graph I’ve drawn below.

This picture nicely illustrates that while it is likely that consuming caffeine will improve your focus, there is a (increasingly declining) chance that this effect is actually (increasingly) stronger or less strong than for the average human being.

This observation is particularly pertinent in cases where the normal distribution extends beyond the border between a net-positive or net-negative effect. In such cases, there might be a chance that consuming caffeine will negatively influence your ability to focus. Consuming coffee may, in your case, be detrimental to your self-improvement objective!

The importance of self-administered experiments

We can try to find out the effect for ourselves by conducting a self-administered experiment.

A self-administered experiment is a systematic investigation to understand whether a hypothesis that is generally accepted (and indeed perhaps scientifically established) applies to you specifically as well.

By measuring the effect of an independent variable (e.g. ‘consuming coffee “yes” or “no,”’ or ‘number of coffees consumed’) on a representable dependent variable (e.g. ‘reaction time’ or Heart Rate Variability), we can develop a model that tells us whether we can accept or reject the hypothesis in our individual case. In other words, we can see whether coffee improves our focus or diminishes it.

For sure, all these great behaviours and supplements can have tremendous positive effects on our well-being and health. However, I would argue for a more cautious approach, where we critically evaluate these effects to prevent (1) jeopardising our goals and to (2) save ourselves money (e.g. in the case of supplements) or time (in the case of behaviour). I.e., a personal development culture of self-administered experiments.