Can you remember the last time you thought something really nice of a person, but never even considered sharing this thought with him or her? Perhaps a colleague came up with a surprisingly creative solution, or a friend did an amazing job handling a conflict.

While we can really appreciate these things about others, we rarely let them know. Perhaps we are afraid that the other person will perceive it as a romantic advancement and we want to avoid the awkwardness this would entail, or maybe we think the praise is obvious and sharing it will only make the other person feel diminished rather than elevated. Maybe we are so caught up being impressed that we simply forget to voice our admiration. There are many reasons much praise remains unheard, but just as many reasons to start changing this.

They deserve to know (while they still can)

Ok, this first one is a little dark but nonetheless worth sharing. I was talking to a friend about how suddenly someone can be ripped away from life, and how terrible it can make you feel not having said the things you wish you would have told them. How important they were to you, how much you appreciated their trying… Shouldn’t we all make sure that the other knows we see what is good in them?

Create an atmosphere of appreciation

That same friend also mentioned how unfortunate it is that, while most people are kind at heart but keep it quiet, the few who spread negativity seem to be the most vocal. This, combined with an already present negativity bias1 draws a map of the world as a not-so-kind-place. By vocalising positivism more often, we can literally contribute to a better, brighter world.

Being kind makes you feel good

Being kind makes you feel good—literally. Part of my research on finance draws on something that in the psychological domain is known as a ‘warm glow feeling,’ in which the reward area of the brain is activated and dopamine is released. This warm-glow feelings is exactly what you experience when you share appreciation or kindness with someone else. What’s interesting is that some of the reward areas in the brain become even more active when the kindness is altruistic, i.e. when it is not done with the intent of getting something in return.

I find the latter particularly fascinating, because it does not really make sense from an evolutionary perspective. Somehow, we are simply ‘wired for goodness.’

A shift in perspective

This one may appeal more to me than to others, but by thinking about and sharing what we appreciate in others, we shift the focus away from ourselves.

I’m currently working on a few pieces on (over)identification, where we basically try very hard to perceive ourselves from the other person’s perspective. We all develop this habit from the moment we are born, but some of us may overshoot and become (unconsciously) obsessed with the other person’s point-of-view.

As I will argue in those articles as well, we can break from this somewhat ‘self-centered’ behaviour by consciously shifting the direction in which we perceive. Looking for the goodness in others and sharing it vocally shifts the focus away from ourselves.

The responsibility for receiving nice things

I mentioned before how we may worry about how our ‘acts of kindness’ may be received, particularly in the context of romantic advances. Here, I briefly want to note that while sharing kindness is completely within your circle of influence, how the other perceives it is not.

Surely, we can think about the best moment and words to share it with, but don’t let the thought about the ‘implications’ paralyze you and prevent you from becoming a beacon of kindness. It is simply not within your control.

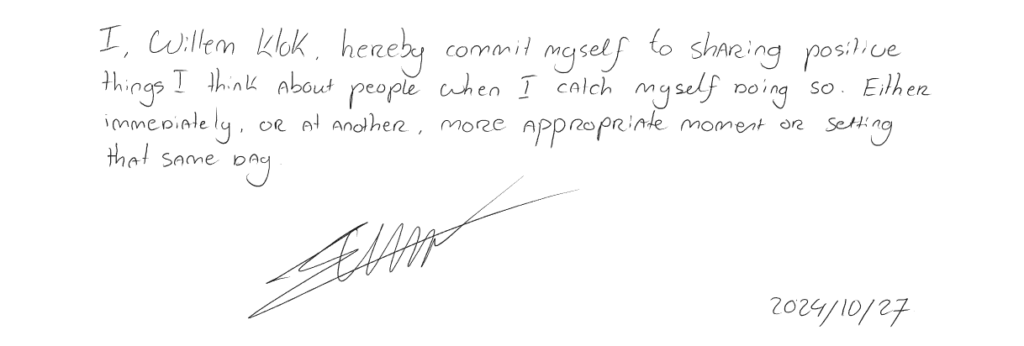

Hopefully this convinced you to vocalise your thoughts of kindness and admiration more often. I, for one, will make a commitment to sharing the light in others I see:

Will you join me in trying to make the world a kinder place? You can share your commitment in a comment below!

Footnotes

- a bias where people pay more attention to negative information than positive, leading to a skewed perception where negative interactions stand out more. In social settings, this bias can cause people to remember negative behaviours more vividly, leading to an assumption that negativity is more common than it truly is.