During the recent COP27 of Sharm-el-Sheikh the need for finance in the energy transition was emphasized once again; we need 4 trillion dollars per year ($4.000.000.000.000) until 2030 if we are to meet the 2050 CO2-targets.

While a lot of money in the absolute sense, it is only a fraction of global GDP (4.2%), especially when you consider that doing nothing will cost between 11 and 14% in damages1.

While a lack of climate finance is one issue, the continued investment in fossil fuels and related industry is another.

In addition to their climate impact, these investments are also a great threat to the financial system.

A study published in 20182 has already shown that a large share of the investments at that time were not going to yield more than their investment value.

A decade ago this notion was still up for discussion, as the value of fossil fuels and related industry was heavily subject by government policy.

By now this is no longer relevant; even when governments remain idle, rapid technological development will produce cheaper energy solutions, making the costs of extracting fossil reserves exceedingly uncompetitive.

The 'carbon bubble'

With the continued investments in fossil fuels and industry we are dealing with an ‘inverse financial bubble.’

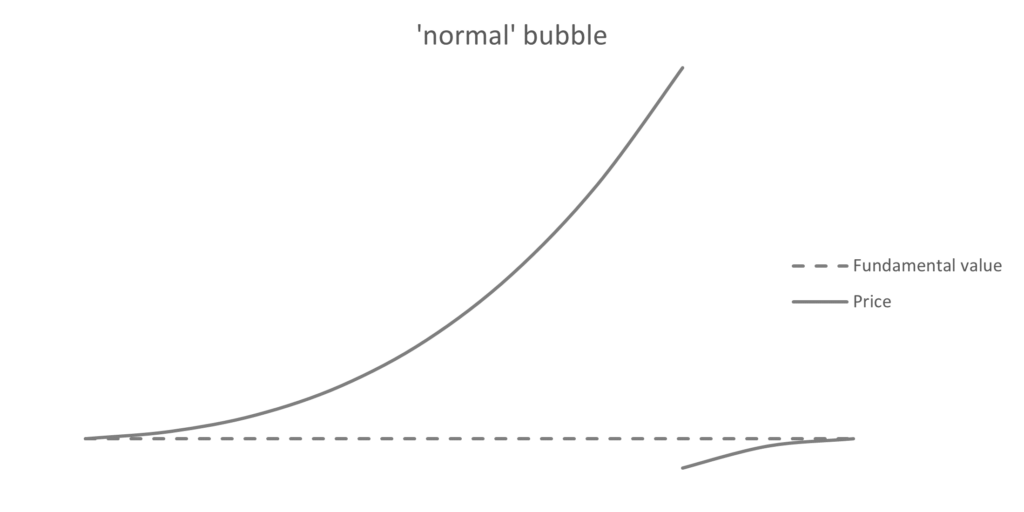

A financial bubble is said to occur when the price of an investment or asset exceeds the investment or asset’s fundamental (real) value.

This fundamental value is the (expected) value the investment or asset is going to bring over the course of its lifetime.

In a perfect world of perfect rationality, you’d expect no one to pay more for anything above its fundamental value (whatever that value may be).

In reality this is, of course, hardly the case.

Even when an investor finds a price exceeding the fundamental value, there is still a rational incentive to make the investment, namely the expectation of being able to sell the investment at a higher price in the future.

When enough market participants behave this way, they can collectively drive up the price.

Though, at some point, the risk (that no one is going to buy the investment at a higher price) becomes so large that the investor exits the market.

When other market participants follow suit, the current owners of the investment are left with an overvalued asset, no one is willing to buy it for a price even remotely close to what they paid for it.

The bubble pops and the price implodes and settles to a value near the investment’s fundamental price.

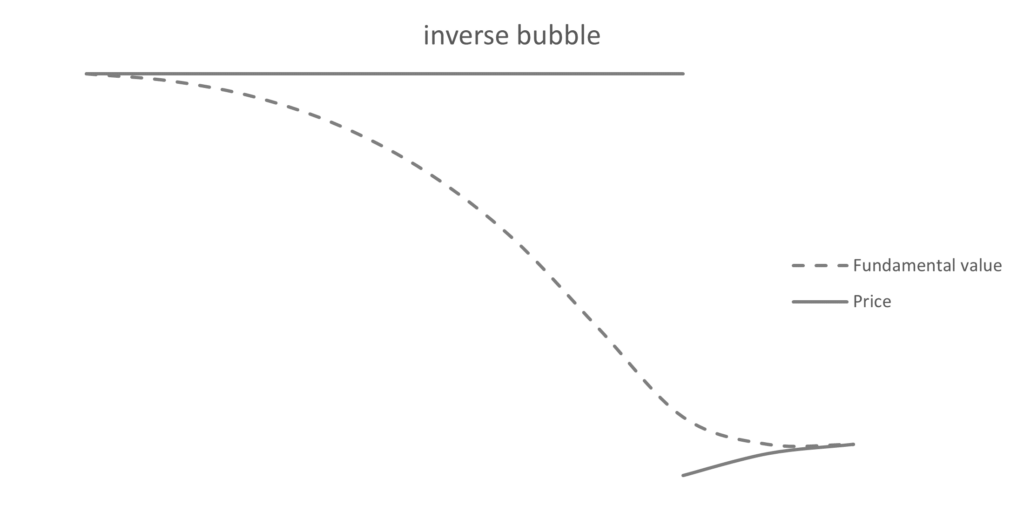

In the case of fossil fuel and industry investments, the situation is a bit different (see image below). It is not the price that goes up but rather the fundamental value that goes down.

The outcome, however, is the same; at a certain point in time the risk becomes too large and no one wants to hold the investment; the bubble pops.

If this were to happen with the volume of capital currently circulating in the fossil fuel industry we can prepare for another financial crisis, about 2 or 3 times as large as the crisis from 20083.

Enough reason to sound the alarm, from both a climate and financial perspective.

The challenge: finding the why

Why does the market fail to anticipate this gloomy prospect? And what can we do to change this? That will be the overarching theme of my research project.

The project has four distinct phases on which I’ll briefly elaborate below.

Phase 1: definition of the transition system

To align finance flows with the climate targets a transformation of the financial system is required4.

In order to imagine such a transformation, we first need to have a clear picture of the system under transformation.

In the first phase of my research project I will be using transition sciences to describe the financial system.

What are the different investment philosophies (niches) and how does that affect the emerging market behaviour (regime)?

How do these components influence each other, and how are they affected by landscape signals, such as the market system and rating agencies?

Phase 2: Investment philosophies

I will complement a literature study with finance expert interviews in order to understand the workings of the various investment philosophies identified before.

What information do they base their decisions on (market trends, company performance, social responsibility scores)? To wat extent do they look at the competition? What external or market events are they looking out for?

When we better understand these considerations, we can also determine which external forces can have an effect on the transition system.

We use cognitive maps to quantify investor decision-making, which allows us to combine the different strategies in a single agent decision-model, which we will use for our simulation inputs in phase 3.

Phase 3: simulation model

The goal of this phase is to develop a simulation model that is able to reproduce real-world market behaviour.

Here, the goal is not to be able to do accurate price predictions, but rather to see they type of market responses to specific situation.

Examples could be the response to an imploding bubble, or the transition from one industry to another.

To meet this end, we should look beyond the common equilibrium simulation methods and find something that can be used to model actual transitions.

One method particularly suitable is Agent-Based Modeling (ABM), which does exactly what the name implies.

In agent-based modeling, you really only model the playing field (system boundaries), the players (agents) and the mutual interactions. After that, you basically let the model play out the game.

By changing the rules, playing field or agent interactions, you enable yourself to reproduce certain events, and compare the emerging responses.

When the model appears to mirror reality sufficiently well, the model can be used to estimate how the system might respond to certain (novel) interventions, e.g. a law.

In my model I will use the typology of the first research phase to define the structure and interactions of the system and the second to help define the rules for agent behaviour.

Historical market trends can be used to evaluate the performance (how well it reflects reality) of the model.

Phase 4: interventions

In the final phase of the research project we will use the model to evaluate various market (policy) interventions.

What would happen when investors are forced to pay an additional fee when they want to sell their investment closely after buying it?

Or what happens when fossil investments due to a higher CO2-tax also lose a lot of value in the short-term? And when the price of fossil assets would suddenly drop by 10%, if and how would the market respond?

Again I should stress that we aspire to observe possible emergent market behaviour, not for price prediction, but rather for pattern analysis.

By providing insight in possible market responses, financial authorities and governments can make better-informed decisions.

I will start with the first research phase in January 2023, and hope to share some of the intermediate results as well!

Footnotes

- Swiss Re Institute, ‘The economics of climate change: no action not an option’, Apr. 2021.

- J.-F. Mercure et al., ‘Macroeconomic impact of stranded fossil fuel assets’, Nat. Clim. Change, vol. 8, no. 7, pp. 588–593, Jul. 2018, doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0182-1.

- C. Flavelle, ‘Climate Change Could Cut World Economy by $23 Trillion in 2050, Insurance Giant Warns’, The New York Times, Apr. 22, 2021. Accessed: Oct. 18, 2022.

- P. Pauw, D. Dasgupta, and H. de Coninck, ‘Transforming the finance system to enable the achievement of the Paris Agreement’, in Emissions Gap Report 2022: The Closing Window, 2022.