To make our infrastructure and economy more sustainable, billions of euros in investments are needed each year. However, these investments are lacking because some fundamental aspects of the financial system and sustainability are directly opposed.

Sustainable finance’ seems to be the miracle cure, but—as I will show in this article—it actually worsens the situation. With the current laws and regulations, a sustainable future is moving further out of reach.

Is there an alternative?

The modern-capitalist financial system

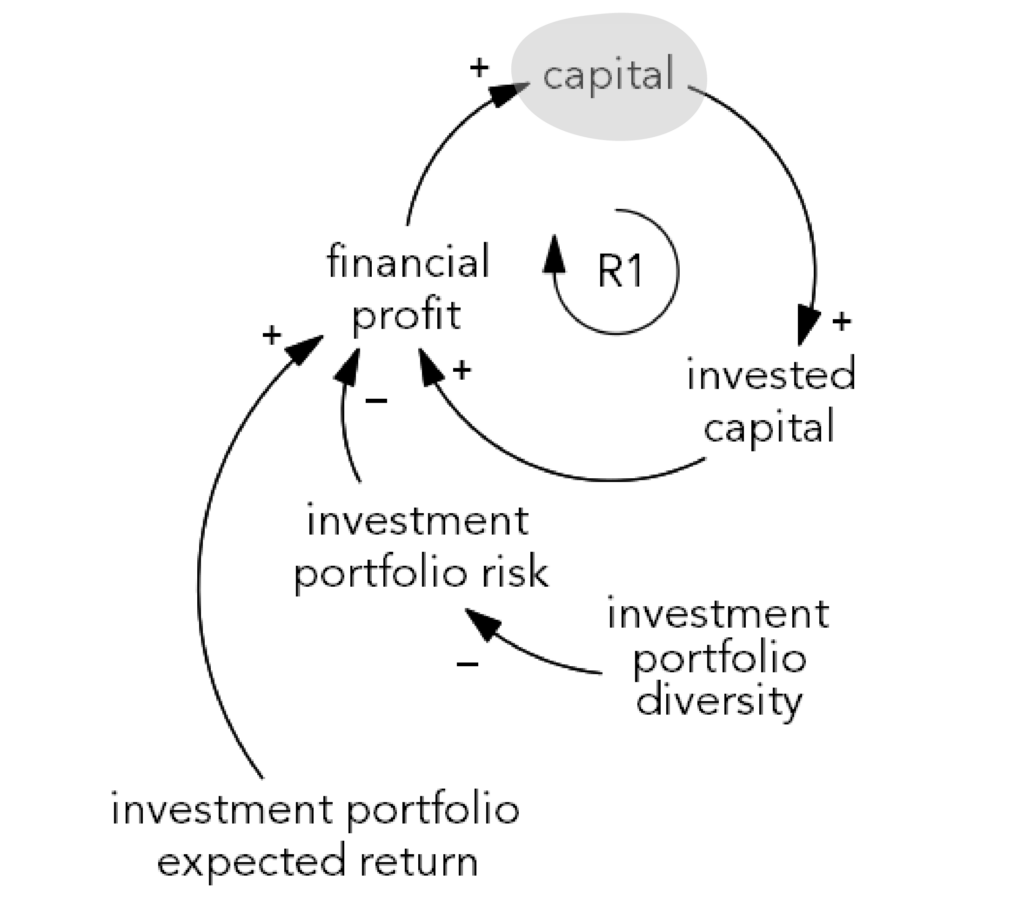

To understand the fundamental mismatch between the financial system and sustainable financing, we need to look at the bigger picture. To do this, I have provided a very simple model explaining how investors make decisions under the current financial regime.

The goal (highlighted in gray) is to increase capital—to make a profit. This is done by using capital to acquire the most profitable investments and minimizing the risk that the profit expectations are not met. To achieve this, we have seen a shift towards ‘passive investing’ in recent decades, where you invest a very small amount in a wide range of (different) things. A diversified portfolio is less risky, according to Markowitz’s mean variance portfolio theory.

The goal of the current system—to maximize profit—contains several aspects that fundamentally clash with the underlying principles of ‘sustainability.’

First of all, the highest financial return is achieved by extracting as much value as possible at the lowest possible cost.

At the moment, this can be done quite effectively through deforestation in South America, intensive agriculture and livestock farming, and manufacturing clothing in places where laws on working conditions and minimum wage either do not exist or are not enforced.

Secondly, you preferably want to extract that value as quickly as possible.

If you acquire capital earlier, you can invest it in something new sooner to further multiply it. This is the loop in the top-right corner of the diagram. It is entirely justifiable to deplete a piece of land in two years, even though you might have been able to do much more with that same piece of land over a period of ten years. At least, from the perspective of the current financial model that is.

Exploitation and short-termism. These two elements are fundamental components of the current financial system, but they are in direct conflict with what we understand as sustainability (long-term and value preservation). As long as this system remains in place, a sustainable future will remain an illusion, an idle fantasy. A fundamental transformation is necessary.

Financially-driven sustainable finance

The failure of investors to contribute to the sustainability transition is acknowledged by governments worldwide. Especially here in Europe, many significant laws and regulations are already in place or coming into effect. Think of pricing emissions (mainly CO2), mandatory reporting of non-financial data, tax benefits for green investments… There’s a lot happening.

Although practice often lags behind, I certainly won’t deny that these developments can have a positive effect on the flow of money for sustainable investments. However, they do not change the fundamentals of the current system. Exploitation, preferably as quickly as possible, remains the essence of the financial model.

Again, a model fundamentally incompatible with a sustainable future.

CO2 pricing only helps to make the outcome of the current value calculation more favorable for the more sustainable alternative—the definition of ‘value’ does not change. Publishing non-financial data enables investors to make their current models even more precise—the models do not change. The tax benefit merely reinforces the idea that financial return is the determining factor—the purpose of investing does not change.

By providing tax benefits for sustainable investments, we are essentially using taxpayer money to compensate for the financial returns that green investments lack because they do not exploit people and nature. Indirectly, we all end up paying for the companies that continue to uphold the culture of exploitation.

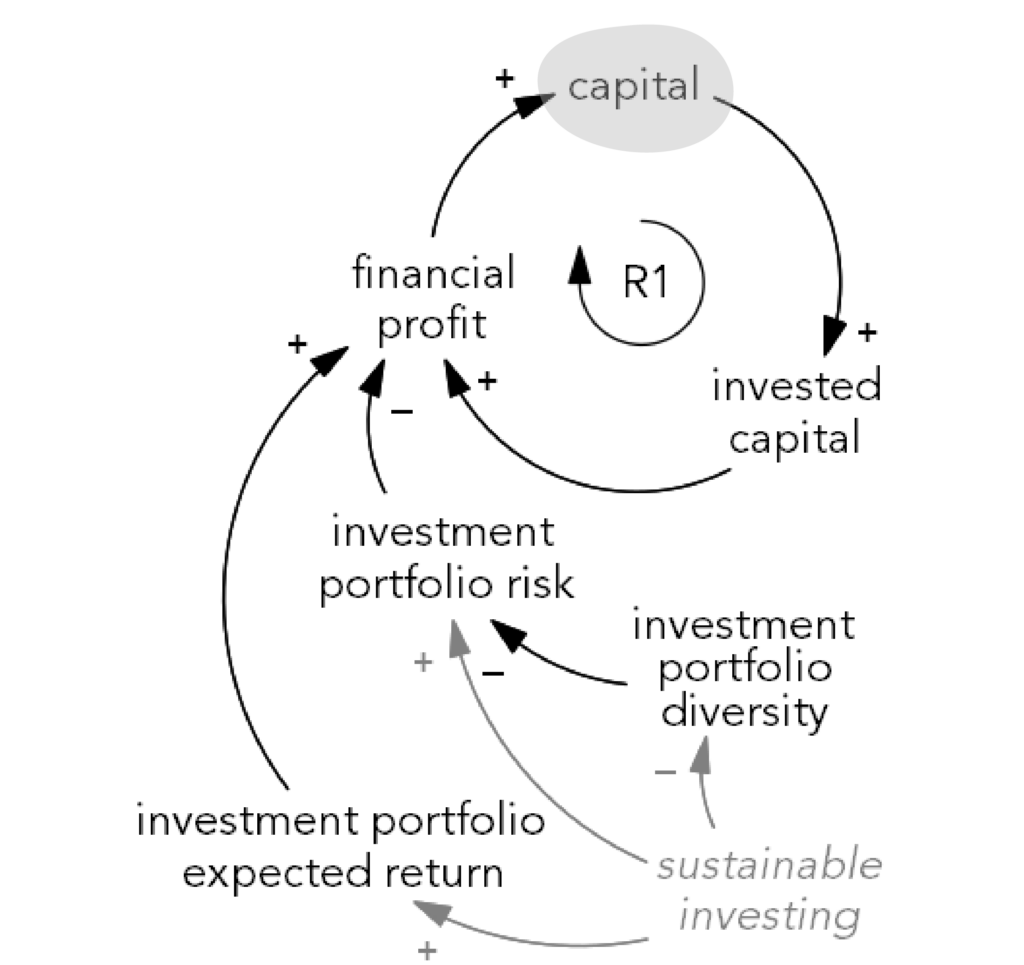

This is also reflected schematically. We are merely adding new elements to the current model without changing its fundamental, anti-sustainable aspect. Investors will continue to look for opportunities to extract as much value as possible at the lowest cost; we’re just tweaking the numbers they use to do it.

Investors might choose greener options more often, but only if it leads to higher financial returns and does not significantly compromise the diversification of the investment portfolio.

To me, that doesn’t quite sound like it matches the urgency that the climate crisis demands.

Sustainable finance: a Trojan horse

It’s not unreasonable to think, “Okay, these rules may not be perfect, but at least they encourage some much-needed investment in a sustainable economy!” There’s something to be said for that, but by building even more laws and regulations around the current system, we’re only making it more resilient to change in the future.

The financial crisis of 2008/9 made very clear that the current financial system had become too large. Houses have stopped being homes; they have long since become an investment that makes a portfolio more stable in crisis-times.

The same is now happening with sustainable investments: emission rights are used as a market diversifier, green investments allow investors to hold onto their fossil stocks’ short-term returns for a little longer, and expensive insurance for hailstorms or floods has proven to present a lucrative business-case.

Because the current laws and regulations take the foundations of the financial system for granted, the system is only further reinforced and strengthened—the motivation for investing further legitimised. Climate change is not being prevented; instead, it becomes a new opportunity for financial returns.

In short: Sustainable Finance facilitates the financialisation of our climate.

Financialisation means the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of the domestic and international economies. (see Epstein's 'Financialisation and the World economy.')

Expressive-emotional returns

It is difficult to imagine a financial system that is not driven by short-term capital accumulation. After all, it’s inherent in the name.

But in addition to the aforementioned developments in financial regulation, there is another, much more powerful change underway.

For certain green investments, we see a growing gap between what (mainly private) investors are willing to pay and the actual financial value of those investments.

What this tells us is that owning sustainable investments, in addition to the financial aspect, also brings some kind of non-financial value.

Considerably less research has been done in this arena, but a reasonable approach to understanding this value is that owning a sustainable investment has expressive and/or emotional benefits for some.

In such a case, it helps to view the investment as a product, like a car: driving a Prius1, for example, expresses environmental consciousness (value) and gives a sense of virtue (emotion), while driving a Bentley conveys status (value) and gives a feeling of pride (emotion).

From the literature in marketing, consumer psychology, and behavioural economics, we know that this ‘utility’ manifests both at the time of purchase (decision utility) and during its use or consumption (consumption utility). In the case of sustainable investments, this consumption utility may, for example, stem from the impact the investment is perceived to have made.

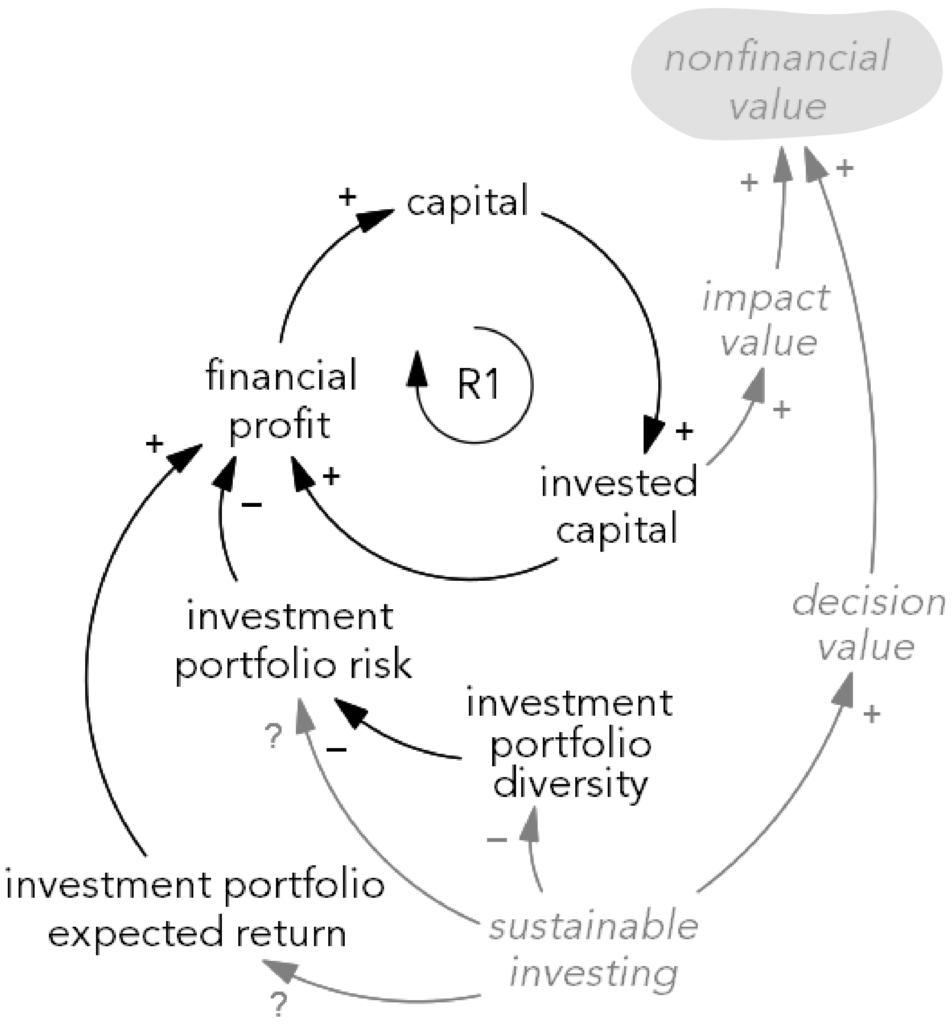

If we take maximising this form of value as the guiding goal in our model, we end up with a very different picture:

Financial returns are still part of the model, but only as long as they are subject to generating impact—or ‘value’ in the broadest sense of the word.

Capital and the financial system become a mechanism for creating value, rather than for extracting it.

A system like that may still seem far-far away, but there are several trends that confirm its growth2. The hopeful part is that this movement stems entirely from investors’ own motivation, not from laws and regulations or better financial returns.

Utopia or not, exploring how we can create expressive-emotional value seems to be a worthwhile endeavour. And who knows, we might stumble across the beginnings of a fundamental transformation of the financial regime.

This article is based on a scientific manuscript I am writing, drawing on transition studies, system dynamics, and leverage points. Do you know of a multidisciplinary journal that would be open to such an article?

To better develop our understanding of non-sustainable returns, I would like to collaborate with a sustainable bank. Do you know anyone who works at such a bank?

Footnotes

- Note that this value is subjective: it says nothing about whether driving a Prius hybrid is actually good for the environment.

- Social banks such as Triodos Bank (Netherlands), GLS Bank (Germany), and The Co-operative Bank (United Kingdom) are growing faster than conventional banks. Moreover, the green premium (also known as 'greenium') that investors are willing to pay for sustainable assets continues to increase. Recently, the largest European pension fund (ABP) began liquidating the fossil fuel stocks in its portfolio, for both financial and moral reasons. This underscores that this trend also applies to institutional investors.